The Oldest Part of the Brain

Consciousness has been found to reside or connect in the oldest part of the brain. Not the fancy new parts, but the worn, comparably plain, uncelebrated part, the stem.

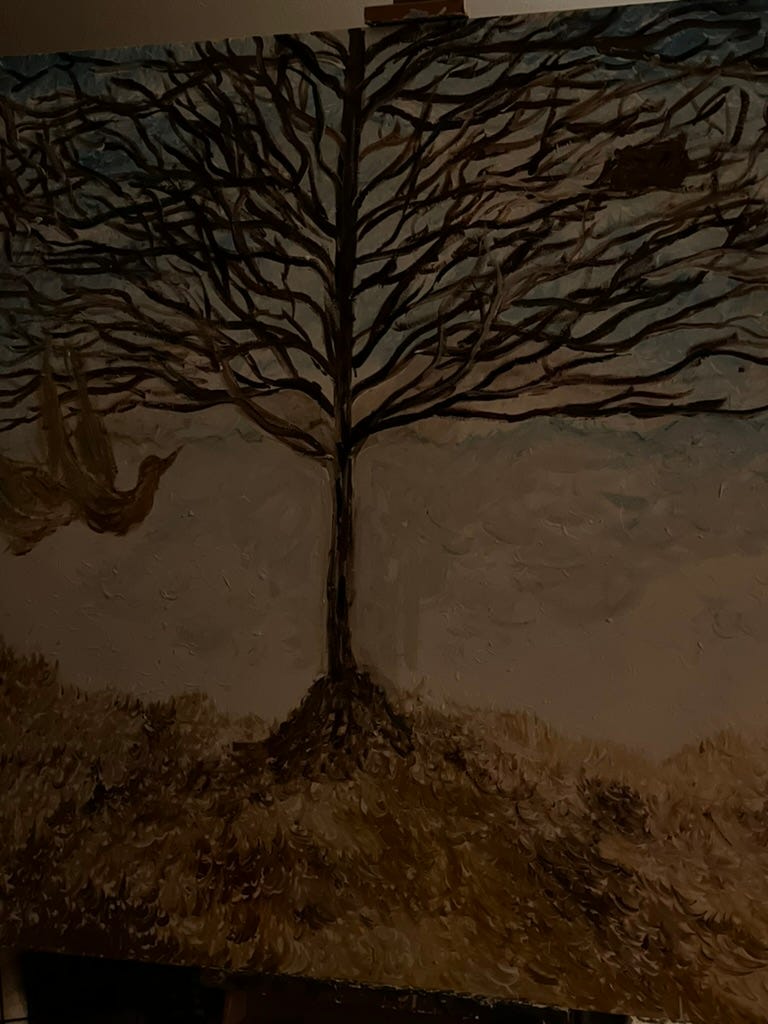

This is how far I got into a new painting on October 31, 2022. I was thinking of a dog named Django, a beautiful, drooly yellow labrador who belonged to a couple of musicians who have a cottage on the same bay off of Georgian Bay as my family’s cottage. Django had died, and I was grieving him by painting his fur which turned to golden grass on the canvas. All his colors in all the different qualities of Georgian Bay sunlight spelled him out for me— an earth. As the mound in the middle formed, I knew a plant of some kind was growing. I gave it some form. Then I went to bed.

On the following day, I would drive my mom to Chapel Hill for medical appointments. I would overdo everything as I always did— talk with a student about leading the class I would miss, submitting photos of paintings to a grants organization after settling into our hotel. The next day, the 2nd of November, we would attend the appointments then drive home. During the drive I attended a faculty assembly via Zoom followed by a Storytelling class via Zoom as well. I dropped my mother off at her home in Swannanoa then returned home where I slipped while feeding dogs and begin my journey through post-concussive syndrome that would render me functionally blind for seven months, an brutal sentence of utter darkness and barely functional cognition. I spent every day hiding from every shard of light.

My brain felt like the little start of a plant or something. This image remained on the canvas for the first two months. It was a self-portrait of every thought I tried to have.

I remember being there. A part of me remembers. Most of me wasn’t there. Much of me didn’t come back out into light. I was winnowed, a bare stem of myself. Writing about it now moves me back into shadow, the place I am still most comfortable. When I get one of the headaches that ceaselessly pummeled, stabbed, and sruck me returns, often with an instant of something like blindness, I don’t mind at all. I wince. I cry out sometimes. I worry one will happen when I am driving. The greater effect is humility. I feel I could be sent back there without a moment’s notice. I feel I am still there. What everyone sees is me doing my me thing.

I was slow in the dark. I was nameless. The damage to my occipital lobe, the part of the brain that makes sense of seeing, turned my world inot a magical, majestic even, excruciating place. The floor could vanish mid-step, revealing nothingness it was too late to avoid stepping into. Dogs flew. Things perceived in the dark congealed and wove shadows of shadows. Sometimes I would pretend-watch TV on lowest light. No short term memory meant not following the plot on a whole new level. With resets every 60 seconds, life was not continuous. Sometimes I was there. Most of the time I was missing from myself. “You have a brain injury. That’s why you don’t know anything,” I explained to myseld in black dry-erase on the fridge. I’d nod at it, unsure if it was for me.

Time withdrew. I knew I taught on Tuesday evenings and Wednesday afternoons. Other than that, there was day—when I recoiled in my bedroom or the darkest corner of the living room. There was evening—when I could feel the outer edges of my burning frame dim a little. I rememember that relief. Like an animal outwitting a predator, I slowed my breathing once I’d made my way to safety.

Having light as an enemy imprinted a fear. Hashem, my dear friend Harlan taught me, speaks of the Name for God which we cannot say. For years before the injury, he would comment “Hashem” in regard to photographs I shared in which light created beauty. I came to equate “light” with Hashem, with God and would notice light with interest: what it was doing, how it behaved, where it shone in surprising places. Light, this thing we the sighted see with all the time and seldom see. Part of me believes the injury was an invitation to experience light in another way. When the sun set at the end of the street I walked onto from a meeting one week after the fall, it entered me.

The pain is comparable to childbirth for seven months straight. That pain. Lose your mind pain. While it is difficult to remember pain, much less describe it, I can connect labor pain to brain injury pain through a portal of one to the other. When I was giving birth, I shouted out “Why isn’t anybody helping me?” followed instantaneously with another shout, “Don’t touch me!” In both, I was at the far edge of self. Only one of these pains can be extinguished. The brain pain could not. I lived under it. I obeyed it. I could not run from it because I was it.

The pain, the dark side of light, played an inductive role once the shock of two months in this state settled into a functional acceptance. At that point, music grew in my awareness. It had no source outside my head and was clear and real as any music you hear on the radio with a good signal. It took me some time to formulate the thought: a presence was in there with me. The music was not random. It was songs that related in subtle and direct ways to me, to my situation, to my injury.

“This music isn’t me, is it?” I thought/asked.

“No, it’s me,” said the source of the music, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.”

“Do you like Gordon Lightfoot?” I asked.

“I do.”

“Are you singing this because I am like the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald?

“I am,” it said.

“Are you going to sing all of the verses?”

“Yes,” it said.

“Okay. I’d like that,” I said.

The presence was sweet and beautiful. Honest and without any snark. It was too kind to be human. It was gentle, supportive, and it knew things I could not know, such as a tv show, In the Dark , about a blind woman. In one episode she uses an app that reads a document she holds in front of it, an app I desperately needed and did not know existed. The voice led me to it. The voice led me in other ways. Always there. Always supportive. Always company. It never challenged me or chided. For hours on hours into months on months, it was there, and it was holding me. It’s still here. It’s still holding me. It’s why I’m writing all of these essays. I’m writing into it, for it, not just about it.

When I saw the headline of a new study that shows that consciousness doesn’t reside or relate to the “smart part” of the brain but to the oldest, I felt a lovely sense of relief. I have been hanging out in the oldest part of human history since the injury. I have reserached Neanderthals, ADHD chromosomes sealed in casseine which ensures their safe passage through generations, cave paintings, little caches of raspberries concealed in grasses by early humans, the first splinted bone, and the occipital lobe, the only physical feature of the human brain to have undergone change in thousands and thousands of years. I have felt more like an Neanderthal than a modern human living in 2025.

I’m slower now. I’m more challenged in busy spaces. I detest flourescent light. I can spend ten minutes under a particular LED before the pain takes over. I’m quieter. I shield myself from conflict and sarcasm. I am even more introverted than I was before. When I sit still, I don’t think. I’m simply still. Music plays all the time, and I don’t control it. It’s just there all the time. I listen to it. I compliment it. If it’s marimba and saxophone, which it sometimes is, I tolerate it and smile because I think it knows I can’t stand it. It plays itself out anyway, and I feel happy anyway.

This is life in the oldest part of the brain. Consciousness and cognition touch gently and loosely in creativity. You can show up here with an idea of something you’d like to explore or express, place the tip of the pen to the page, and something unexpected will happen. Again and again, all day, it’s “on.” It invites me but cannot force me since it has no form. But it can create conditions that will make me spend time with it, there at the border of now and infinity. It can increase inconvenience.

It can awe me with light. It can cause me to stub my toe with such force as I have to sit down, and it can arrange for a pen and a notebook to appear before me like I’d thought of it. Because it is consciousness, it can fill anything and get my attention. I smile when it does. I am not afraid of it because now I look back and see how ever-present it always was since childhood. I can recognize it now because it’s been so long. I see how all of it makes sense. I rest in it. It has been cracking jokes for 50+ years. I laugh in it.

The headline felt like a witness, like my friend the universe putting a little star on my homework, “Yes, this is what creativity is, and you knew this.” Every day holds another star, a realization, an insight, a pun, a something that keeps me just close enough. I see how my greatest griefs and traumas whittled away at the layers that separated us. I see why I wrote incessantly and sought ever-deeper resonances within, ideas only sound holds together, entire manuscripts while listening to it, never wanted to sever the string.

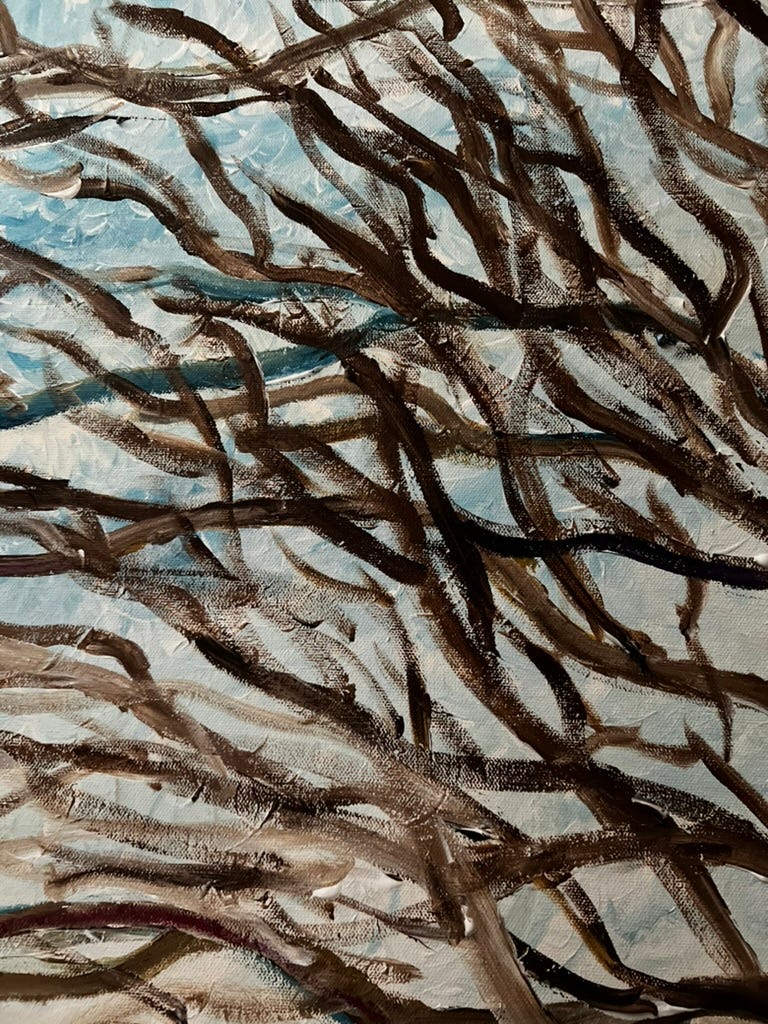

At around Christmas, which terrified me with all its little lights and forced me to hold my darkness even more preciously, I painted. I returned to the little stem of something and with a bold upward stroke, I gave it a tree trunk. Next, I gave it branches. I remember painting them in the low light (through my three pairs of glasses).

I saw the shape of the bird flying toward me and found another painting I had done months before.

This spooked me so I stopped and turned to another canvas on which I had at some point painted a bit of ground and a bit of sky. I thought I was seizing control, but I wasn’t. This appeared.

Then I appeared.

And I stayed with it.

Then I backed off, frightened a little. I couldn’t think still. Everything that happened happened in this other space, the space of encounter. Weeks or a month later, I returned to the Django.

I sensed that the branches were my brain trying to heal. I wasn’t thinking this.

A nest!

A bird!

Then three birds.

The three birds were the lesson of wisdom. At that “oldest part of the brain,” perception becomes three dimensional, and art leads our way, guides us toward it. With creativity, we evolve to origin. We can trust this.