Last Call Cave

a short story

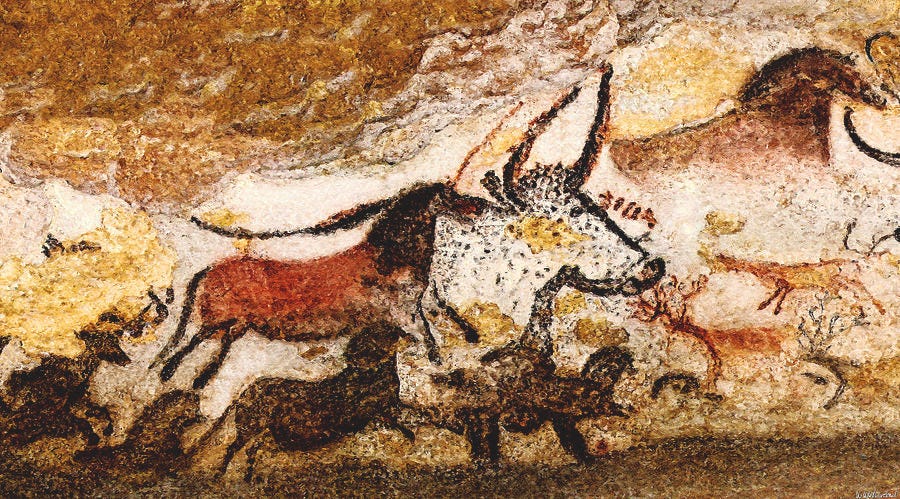

Years before he became a giant, Eric taught Archeology. His heart always raced when he told students the story of how a dog named Robot found the caves when he chased a rabbit into a hole and discovered a system of caves all drawn with plants and animals, a magical world no one but they had known about for seventeen thousand years. When he told the story, Eric always lowered the lights in the room and used multiple projectors to give the students an immersive experience in the small auditorium. It was always his favorite day of the semester, watching his young students' faces light up with the colors of the Upper Paleolithic. He felt it was the screen onto which they projected their history and untold knowledge.

Eric's father died during Eric's tenth winter as a university professor. At the reading of the will, theexecutor handed Eric a handwritten note from his father:

Explore your cave.

The executor then read to the siblings another handwritten letter from their father, Ralph.

Dear children,

You are the light and life of my and your dear mother's hearts. And it is with great sadness that I even imagine the day you read this letter, for when you do I will have left this world and all I love behind in it. My life has not been as I had wished, save for you four, Ralph Jr., Eric, Sam, and Eloise, and of course the love I had for your mother and that she generously shared with me. I had great fiery dreams as a young man, dreams that being in a war tend to quell in a heart and draw their dreamer closer to the bloodstained, echoing earth. I made the mistake of trying to live a safe life, ever prepared for the worst and often denying myself the best. That is, as I've said, except when it came to family. After the war I never traveled. I never took you traveling. I never ate the best food, and the food we kept in the house was moderate at best in quality and flavor. I didn't indulge fancies that your mother often had of renting cabins or going to the seashore. I made sure we had enough but not so much as to excite your senses to the impossible things in life. I wanted you to be safe, and to me that meant making sure you were sane. I made sure you did your homework. I made sure you were home by dark until you were old enough to stay out a few hours after. You were my pride, my joy, my love, my home. I kept you close. It was all I knew to do.

Now, bear with me, there are a few things I didn't tell you about, and I hope you will forgive my delay in doing so, as it was only to protect you from making mistakes that come with thinking you're dif erent or better than anybody else.

The letter continued with the information regarding the possibility of one male in each generation turning into giants. Ralph made it clear that Eloise, his only daughter, need not be worried about the impact this might have on her, save the inevitable additional responsibilities it might pose on her should the abnormality manifest in one or all of her brothers. The three siblings sat in shock as the executor read aloud. By the time he reached the end of the letter with the addendum that each sibling would receive an inheritance in equivalence to $2,000,000 in real estate holdings and cash amassed through their father's unrelenting thrift, they were in a shock even deeper than the first stage of grief. They could not even lift their eyes from the hypnotizing pattern of the Oriental rug on the living room floor, a gift from one of their father's clients, nothing he would ever have spent a penny on.

Becoming millionaires mattered less than waking up one day a giant. Eric inherited the warehouse of the family-owned uniform factory, a path neither he nor his siblings took any interest in. His father knew of Eric's obsession with the caves and had helped fund his research in Dordogne when fellowships and grants weren't enough.

One month later, after giving his father's words about his cave some thought, Eric submitted his resignation in ample time for the university to find his replacement. He paid a man who worked in an abattoir to save and deliver plastic canisters of cow and pig blood, bone marrow, albumen, urine, and fat, which he mixed in water using shoulder bones of the slaughtered beasts. With these materials he replicated the Hall of the Bulls, the rotunda just inside the entrance to the Lascaux Caves. Painting the animals filled him with an energy he had never known. He had studied them for so long that now it seemed he was merely translating them with his body. He moved up and down the tree-limb scaffolding like a hamster in a habitrail, placing pigments in places he seemed to remember from some great collective unknown. He navigated by intuition as the seventeen-foot-long bison emerged from the concrete warehouse wall exactly as it had emerged from stone seventeen thousand years before. He painted on instinct. He painted primordially. He painted wildly. As he completed the mural, all sixty-six feet of its length and sixteen feet of its height and fifty or so of its animals, a woman walked into the warehouse.

"My name is Joan. I own a spa down the street. I heard you were opening a bar and thought I'd come down and say hi and welcome to the neighborhood."

Eric moved forward in time to greet her. He hoped Joan wouldn't smell the blood he was using instead of paint. He was relieved she wasn't from the health department.

"I'm Eric."

"Is that --?"

"The Lascaux Cave."

"Yes, I recognize it from my high school humanities class. The Hall of the Bulls. We had to memorize

two hundred works of art. What are you --"

"I'm an archeologist who lucked into owning a warehouse. My dad left it to me."

"I'm sorry," said Joan, "about your dad."

"Thanks." It was that difficult kind of gratitude that comes with being shown kindness while also

dislodging the thing we don't like to think about. "He was a good dad."

Joan sniffed and wrinkled her nose, inhaling the scent of blood. She dismissed it as preposterous and said nothing. She spotted the small wooden table with papers on it, a license to sell alcohol, an electric bill. "Last Call Cave. Is that the name of the bar?"

"Yeah, it came to me a long time ago. I always thought it was a great name for a bar. So now I'm opening a bar. What's the name of your spa?"

"Om Mani Pedi Om."

"Brilliant. I like it."

They were in her bed on a Thursday afternoon when he told her he might become a giant after she explained that she had pills on the nightstand to manage a chronic illness this and that. Joan had recently rearranged her bedroom so two people could climb in rather than one person, herself, as it had been for five years. She'd hung actual curtains in place of the painting cloths she bought at Lowe's for $20, and she'd brought some lamps from her basement to create soft lighting. Nesting, her mother would call it, but really she was just making the room look like more than a stone hut on a cliff where an early Christian monk would meditate and pray, gazing out over the North Sea, waiting for something to happen.

Afternoon sunlight shone through the space between the curtains, which were tan and white cotton with the French fleur-de-lis pattern. Over his shoulder she studied the pink of a rhododendron blossom.

"Since we are sharing medical information, every few generations," Eric said as Joan propped another pillow under her head, "one male in the family turns into a giant."

He motioned to his own body by running a hand through the air over the pale-blue sheet, four hundred thread count bought on eBay for $25 the previous week. Joan had never had such nice sheets. She didn't realize when she clicked "Buy Now" they were the same color as her walls. Exactly the same color as Eric's eyes. Eric had said, when she noticed this, that it was the universe mirroring her back to herself. As his hand flourished at his arm's full length and returned to hold her own between them, she remembered being relieved by his height on their first date.

"All of a sudden he'll just spring up and add another two feet or more," Joan imagined how it could go.

"To his height."

"Yes, he'll suddenly be two or so feet taller."

"Suddenly."

"Suddenly."

"Like he wakes up one morning and is --"

"A giant."

"Does his body change other than height?" Joan pictured the Incredible Hulk from the 1970s TV show.

"No, everything remains proportionate."

"He doesn't become all gruesome and gruff like the giant in Jack and the Beanstalk."

"No, more like Paul Bunyan."

"Still handsome and whoever he was before."

"Oh, yes, everything remains the same, just taller."

"Much taller."

"Yes, he's just a giant."

"How tall are you now?"

"I'm six-foot-two."

"So if you're the one in your generation, you could be eight feet."

"Suddenly."

"Suddenly."

"You're not the first giant I've met," she said.

"Well, I might be a giant. What other giants have you known?"

"When I was little my father brought a giant home from work one night."

"Where did he find the giant?"

"He was an endocrinologist so a lot of his patients had either dwarfism or, I guess the term is giantism.

When we lived in Florida later on, many had played Munchkins in The Wizard of Oz." Eric now propped

a pillow under his shoulder to listen. "Anyway, my father felt it was important for me to see how many

different kinds of people there are in the world, so he often brought his patients home for dinner."

"Maybe he brought my uncle home."

"This was in London."

"Ah, there are many giants in England."

"In folktales."

"Maybe," said Eric. "So your father brought home this giant."

"Yes, he was so tall he had to hunch over in our kitchen, and at the table it looked like he was standing,

and he never had to ask us to pass him anything because his arms spanned the entire table. He asked

anyway. Pass the salt. Pass the pepper. Just to appear normal and polite."

"So you're not shocked?"

"No, not at all."

"You'd still want to be with me if I'm the giant of my generation?"

"Well, there might be something else about you that does you in for me, but being a giant isn't it."

The afternoon faded into evening. They dressed and cooked. All the time Joan pictured Eric two feet taller. If everything is proportionate in the event of becoming a giant, she figured, then Eric's arms would extend (she tried to do giant math) maybe a foot. His feet would lengthen also a foot as well.

How would he find shoes? She remembered her art teacher friend taught her about an exercise called the seven-headed man, in which she could draw a person using seven circles, explaining that the head is one head, the torso two heads, arms and legs two each, but that left her with short arms and legs.

She needed more heads. Or maybe it was true, and she just didn't understand men the way she ought to.

In the morning Eric scooped three scoops of French Roast into a paper filter, then placed the filter mechanism into the machine. He poured three cups of water into the reservoir and replaced the lid.

His movements were succinct and fluid. Together they leaned against the kitchen island and waited.

She measured her height against his. She felt a bit sad when she thought of herself coming up only as high as his belly button. How would they go to parties? How would he fit in the car? A list of larger vehicles flowed into her mind like a small mountain stream: Humvee, Land Rover. When the list presented Monster Truck, she said, "Are you sure there's no timeline for when you might turn into a giant?"

"There's no telling. Just later in life."

"What if you don't know how long you'll live?"

"You mean what if later just means I'll turn into a giant at a moment in proportion to my unknown death date?" The coffee maker sputtered that last exhale. He poured. "That's a little heavy for morning conversation, don't you think? I don't ask you about when you're going to die."

Joan poured a magnolia blossom of milk into both their cups. Neither liked sugar. "I'm not asking when you're going to die. I'm asking when you'll turn into a giant."

"Is this going to be a thing with you?"

They both sipped. Joan looked into Eric's eyes. They were bright blue, like the edges of a Chagall painting where people and animals fly around. She felt her heartrate calm and her breathing slow. "No, not at all."

The following evening Eric met her at Last Call Cave. A band she hadn't heard of was playing, called The Tallest Man in the World. At least she thought it was a band, but it was really just one man, who was tall but probably not the tallest man, especially for now, knowing that her boyfriend could wake up and be twice his height.

"It plays a trick on me the same way the band called 10,000 Maniacs isn't really ten thousand maniacs," she said to Eric as he poured IPAs for two women then leapt over the bar to join her. They were talking in normal voices that somehow managed to navigate between the notes of the music. "Or the way 99 Pilots isn't ninety-nine pilots."

He followed, "Fine Young Cannibals is a whole other issue."

"I always felt disappointed that these names did not accurately describe the reality. A band was a band, a singer a singer.”

"I suppose the more creative names develop a vastness in fans' imaginations."

"I liked the idea of ninety-nine pilots getting together and singing."

"The pilots with their pressed white short-sleeved shirts under their navy-blue or black jackets, their ribbons sewn to sleeves, little wheely suitcases," Eric added.

"Ten thousand maniacs filling a stage, playing musical instruments!"

Eric paused and pursed his lips before adding, "Band of Horses," releasing an entire herd into the club, surrounding them before vanishing into the replica cave painting from Lascaux on the wall.

"They Might Be Giants," said Joan before stopping herself. When Eric laughed, she laughed too.

Joan felt they had connected on a very deep level.

Eric drew one side of his mouth back, opened his eyes wide, and shrugged as he nodded. "I feel we connect on a very deep level," he said at a volume just slightly above the volume during a louder song. Joan nodded and sipped her beer. The horses remained safely back in place in the painting while the hooves of her heart struck solid earth.

As their relationship progressed, Eric started to come into Om Mani Pedi Om each week to relax. Joan reserved the largest chair for him in case he started to grow. She glanced over at Sheryl, her most experienced and kindest employee, who massaged his feet. If Sheryl winked, it meant Eric's feet were bigger. As weeks passed she developed a reference for which of the little lines on the massage chair his head reached. If his head reached the same spot, all was good. He wasn't turning into a giant yet.

During Eric's treatments she often went into her office so as not to hover. She started going over the accounts in QuickBooks, then found herself googling Giantism, and Gigantism came up. Unusual or excessive largeness. Excessive growth due to hormonal imbalance. Excessive size in plants due to polyploidy. She tried "gigantism late in life" and only got information confirming that height does not increase in adulthood. She then googled a movie she had seen in childhood called Jack the Giant Killer, then Jack and the Beanstalk. She leaned back in her chair and peeked at Eric's pedicure chair and noted that everything was exactly as it had been.

It was the thing they never discussed and the only thing Joan thought about. Eric called her in the evenings to ask her how her day had gone. He asked her questions about Om Mani Pedi Om. She asked him questions about Last Call Cave. What she really wanted was to ask if he was transforming into a giant early. During the day she wanted to text him "How tall are you right now?" One afternoon he called her from the auto body shop, where he was getting a repair done. She pictured him standing in the auto body shop at the corner of Hendersonville Road and Long Shoals, where she could always fill her tires with free air. She pictured the men who worked there, with their kind faces and beer bellies pushing the limits of their coveralls. They always gently laughed at her when she was surprised they didn't charge for air, as though they didn't know every other gas station in town charged a dollar for the stuff we breathe. She worried what they'd experience when Eric started the process. First he'd just be sitting in the plastic chairs fused to metal next to the vending machine, then the plastic would crack suddenly. The people next to him would fall to the linoleum floor, the ceiling panels would crumble as her boyfriend's head reached through to the pink, cottony insulation above. Would he get fiberglass in his lovely hair?

When a new restaurant called The Beanstalk opened in their city later that week, Joan wondered what on earth was going on in the universe and made a reservation. She scanned the corner booths and requested the empty one far from the kitchen. If Eric began his transformation, she wanted him to have space to expand. She also didn't want his suddenly very long legs tripping the waitstaff. Eric didn't ask her reasons.

She simply said, "Booths are cozy." They scooted into the vast booth. "We'll tip double," she assured their server, who eagerly smiled and brought them water. Everywhere she went now, Joan measured everybody's height, very aware that everything she had been told about height, that we reached a maximum by a certain age and that is that, might be a lie.nWhen the server poured a sampling of the shiraz from California, Joan watched his fingers swirl the glass, measuring its legs, as they said. Long legs in a wine were good. His fingers appeared the same size as when they left the car. He nodded his approval and the server poured more into the glass and a second glass for Joan. Things were normal, she felt assured. It wouldn't happen tonight. She leaned back, raised her glass in an unspecified toast, and sipped, smiling at her yet-six-foot-two boyfriend, who asked her for the story behind the name of her meditation spa.

"I learned about Om Mane Padme Om," she began, "from a Buddhist roshi who resided for a semester at my college in central Florida, just twenty minutes from Walt Disney World and EPCOT, which I found to be a peculiar consortium of the most touristic kitsch imaginable with absolutely zero awareness of the suffering that people endured in every nation all around the world. Just look at the pretty parts, it said. At least Walt Disney World called its locations Fantasyland and Tomorrowland. At least it was called the Magic Kingdom, a place that you didn't expect any reality at all from. EPCOT purported to show what real places were like: all of Germany a Heidelberg, all of Canada a tipi and beaver meadow, no Africa at all. Even now park representatives say they hesitated to represent any African nations to avoid war and political infighting, but that was only because Disney planned one African Pavilion, as though Africa was one country while Europe was many."

Eric listened and waited for the part about the roshi to come back.

"The roshi, though, in those early morning meditation sessions in the stone Religious Studies building, made it very clear in her first presentation that the entire world was an illusion. Looking out over the trees of the campus and farther out to the glowing white orb of EPCOT, I'd whisper, 'And nothing is more illusory than you.'"

The food arrived and Eric ate while Joan continued.

"I didn't understand a lot of what the roshi said, but something about her gave me a sense of meaning in the world I had never quite felt I belonged in. Not in a suicidal sense, not in a way that made me want to leave here. On the contrary, it was something that held me to it, how fascinatingly odd it was, how magnificently weird."

Eric felt he was listening to a mirror, if a mirror could talk. He understood exactly what she was saying.

"Weird things happen all the time that people around me don't seem to notice," Eric said, allowing some time for Joan to take a few mouthfuls of her pasta. "Stuff that when I try to make a list of it in my mind, I can't because it was so barely perceptible."

"It's like it had not even registered enough to become memory, the way things people said or did formed memories," said Joan.

"Stuff that I'll catch through the corner of my eye and wonder if anybody else caught it," said Eric.

Their waitperson listened in and could swear that if it wasn't for their different voices, it was one person talking to itself.

It became clear in this conversation that both Eric and Joan, in order to proceed through their days, had been tamping all this down, keeping it to themselves, or else they would just be two constantly amazed people nobody could relate to.

"I was always like this," they said at the same time.

"I was the first person classmates came to, though, when they needed help understanding symbolism

in short story or a novel, or help interpreting a poem."

"Same for me with history and geology." They both felt what was happening. Eric said, "Tell me more about the roshi."

"At the time I wasn't fond of meditating at all. All it did was show me how crazy I might be. Thoughts and dreams didn't drift gently past on my breathing, to which I was supposed to gently return as the roshi taught us. 'Become the cold and you won't feel cold,' said the roshi in her soft German or Swiss accent. 'Become the menstrual cramp and you won't feel the menstrual cramp,' the roshi said when I tried to make an excuse not to sit on the hard cushion for thirty minutes in the cold building with myuterus screaming for heat and lying down. 'You are here,' replied the roshi. 'You are here so be here. Be brave and gentle with your pain.' I felt hatred for the Zen teacher, even though I knew I had drawn myself out of bed for a reason. I could have stayed in bed. That was the beginning of my seeking, I guess, the feeling that something was beyond everything, even if getting to it felt awful. Something inside me had taken over, and it would relent only for brief passages from which I'd return again and again, apologizing to the long-moved-on teacher."

"What's the most valuable lesson she taught you?"

"'We are like bubbles in a stream,' the roshi had taught me one afternoon when I drove her to a grocery store for provisions in the guest apartment the college provided. 'We meet, we become one bubble for a time, then we become our own bubble again.' I had asked her if Zen roshis can fall in love, seeking some rest from the angst I felt when my boyfriend ditched me for another girl with less going on in her life than I had going on in mine, which hadn't been a lot. He and the new girl had sex on a tour bus to a rowing regatta. I couldn't get the image out of my mind. I had really liked him.

"'We fall in love all the time,' said the roshi. 'We are all always falling in love. We just don't land in it.' I wanted to pull over, not just from the road we were on but from the whole road of the world. I had landed in it. 'How do you unland from it?' I asked. That was the day the roshi taught me the mantra that now is painted in pun in Sanskrit-looking English letters next to the door of my shop, with the original Sanskrit over the door. Let go. Let go. Let go."

"I've landed in it," said Eric.

"I have too," said Joan.

Falling in love came as easily to Joan and Eric as falling through a hole in the earth into a system of caves had been for the dog named Robot, the first discoverer of Lascaux, which had merely been chasing a rabbit in the underbrush. Slightly disoriented at first, Robot entered extreme disorientation when his human arrived with a small oil lamp and illuminated the vast swaths of dream surrounding them. Robot couldn't even remember how to bark. Everything was so immense and hurrying and surrounding and, somehow, bestilling, for Robot felt a connection to the bucks and the oxen and the aurochs that he had never even thought about before. He ran the length of the caves back and forth, running with his herd, his pack, his long-lost family of four-leggeds, across the vast plains of unconscious canine existence. As he ran he heard their calls, their whinnies and snorts, and the thrill was so great that every day for the rest of his life, he ran with them, even when he slept by his human'sside as they both guarded the entrance to cave. This is how time felt for Joan and Eric for the next ten years, until their dog passed away when their children were in eighth and ninth grades, prompting Eric's transformation into a giant.

After two years of going out for dinner together, Joan no longer thought about Eric's height. They settled into a peaceful rhythm of a life together. They adopted a dog from the Humane Society and named him Robot, after the dog that discovered the Lascaux Caves. They met Robot at the shelter through a pane of glass first, then in an Astroturf play area enclosed by cinder blocks. Robot only saw large animals on cave walls when Eric and Joan stepped toward him, knelt, then invited Robot to jump into their arms, which Robot did without thinking. Robot smelled the musty cave air on the pair of humans. Robot heard the hooves of distant and not-too-distant animals in their blood. When Robot pressed his ear against Eric's heart, Robot's own heart synched with it, beat for beat. He pressed his ear to Joan's, and he synched them all together.

Eric and Joan traveled to Dordogne and to Lascaux for their honeymoon. Using his credentials, they were able to explore alone the underground prayer to animals as tourists had been forbidden from doing for seventy years. During the trip the caves became a part of their story. Back at their home, when they closed their eyes to kiss, the backs of their eyelids filled with images of horse-like animals, buffalo-like animals, deer-like animals, some expanded to gargantuan proportion while others, though of similar species (what were the species back then, they both sought to know), were small, small, small, and no one will ever know why. When Joan and Eric made love, they met in ancient timelines and found themselves surrounded by hooved creatures running. Sometimes they became the hooved creatures and ran with them, sometimes they chased them, others they were chased by them. They did not speak of this when they nestled together after, returning to the acceptable politeness of everyday life. Eric sometimes saw a doodled antlered mammal on the edges of Joan's handwritten grocery list.

Joan sometimes saw one on a Post-it next to her computer keyboard and couldn't recall if she drew it or did Eric. Sometimes the images appeared on the magnetic whiteboard on the fridge, and each thought the other had drawn it. Sometimes the images disappeared and each thought the other had erased it.

They moved into Joan's house because it had higher ceilings than Eric's and an open floor plan that would come in handy when Eric became a giant. They decorated their home with murals of Lascaux in the colors of bodily fluids. Nonpathogenic acrylic paints using the right blends of burnt umber and burnt sienna and yellow ochre hue proved to be decent substitutes, as maybe he should have done at the bar, but the health department had yet to ask. They talked about having children one day. Robot, the dog, watched by the Lascaux animals Eric and Joan had painted on the walls of their home, thought, I'd like to stay here forever. Undetected by any humans in the home, an ear twitched, a maneshook. In the afternoon Robot lay on the floor near the giant bull. Joan and Eric thought he might have a crush.

Robot died naturally and peacefully on the cool-tiled bathroom floor in his sleep at three in the morning. Joan and Eric both woke up and knew. Their kids, Milo and Wendy, found them still sitting and sobbing on the bathroom floor hours later when breakfast was nowhere to be found. The family of four spent the day on the bathroom floor while the sun arced the sky into evening, when Wendy and Milo got up and brought their parents some food. Together the family painted many Robots into theherd on the living room wall.

Two days passed and Joan said to Eric, "We have to bury the dog."

Eric put his hands to his face and pulled them down as though removing a mask, but there was no mask, just the same defeated, bereft face that everyone wore during that week and for the many after.

Eric and Wendy dug the hole at the end of their garden. Milo and Joan crafted a wooden coffin they all covered with paintings of the Lascaux animals. At the gravesite they all chanted "om mane padme om" once Robot was lowered into the earth, covered, and left as the family went back inside, enclosed in a cloud of earth-toned grief that ran herd-like through their blood as they moved across the grass to the softly glowing interior of their home. Let go. Let go. Let go.

Eric's grief went bone deep and set the transformation in motion.

"The bones grow first," Eric recalled his father's words in the letter the executor read in their living room as first his left femur, then his right extended, causing his feet to strike the floor once his kneecaps and shin bones lengthened. When his spine followed he screamed in pain. Joan held him as he grew two feet taller and all his limbs lengthened.

"This is it. It's happening," she said to herself. "I am here," she said to Eric.

"It's pretty neat that the house you bought on your own actually is just the right size," said Eric between growth spurts. Joan nodded. She had wondered about that as well.

"Maybe we were supposed to find each other," she said. "I mean, not just because you're a giant."

"I guess we always knew that."

"The kids will take some time to adjust. They'll be fine. We'll all be fine." She remembered her

Buddhist reading: Everything is workable. Even this." “The important thing is that we keep them at the center of attention while everybody around us adjusts. The children always come first. Wendy has her student council election. We can't let your becoming a giant overshadow that."

"We will do our best. We always do." He screamed in pain, and the young teenagers ran into the room to see if everything was okay.

"Daddy's turning into a giant," said Joan.

"I'll be okay," said Eric. "Everything will be okay." He then screamed in pain and grew the final few inches, bringing him to a full eight-feet-two-inches in height.

It was at that moment that they heard their dog bark. At first it wasn't startling, but once they remembered that they'd buried Robot the night before, they looked at each other, then all four walked down the hall to the living room. Several of the animals they all had once painted on the walls now walked around the house like it was their home or like the house was all wilderness. The walls continued to expel them as only tiny footprints and massive footprints remained. Their paleolithic fur emitted strong odors, but other than that they were perfectly like animals at a zoo, except the extinct ones. It was a lot for the family to fathom and even more for them to feed. When little Robot came barking up to Joan and Eric and the children, Eric wrapped his massive arms around them all as Robot curled up in Milo's lap, then Wendy's. Then the other Robots they had painted on the cave walls (they hadn't considered this might happen) came running up to the family as well, nosing their ways between the hooves of the other beasts. The walls were now bare of anything but outlines as the animals found their way through doors into the greater world.